By Devin Pettigrew, 4/24/2020

As described in What is an atlatl and how does it work?, the atlatl is a lever that provides more control and a little more velocity on the projectile. Atlatl darts don’t hit harder than javelins, but atlatls do require less strength and probably less training to become proficient. They also slightly increase the effective distance for hunting. But advances in weaponry come with other costs; namely more complex tools require more time and effort to manufacture and maintain. Cultures that place more emphasis on skillful operation (such as getting close to prey) than production may be less inclined to transition to new tools (Cundy 1989). Other factors could cause new technology to be adopted or rejected. If something works, why replace it? The development of the atlatl matters, but first we need to think a little more about the historic contexts of weapon advancement.

Advances in weapon technology

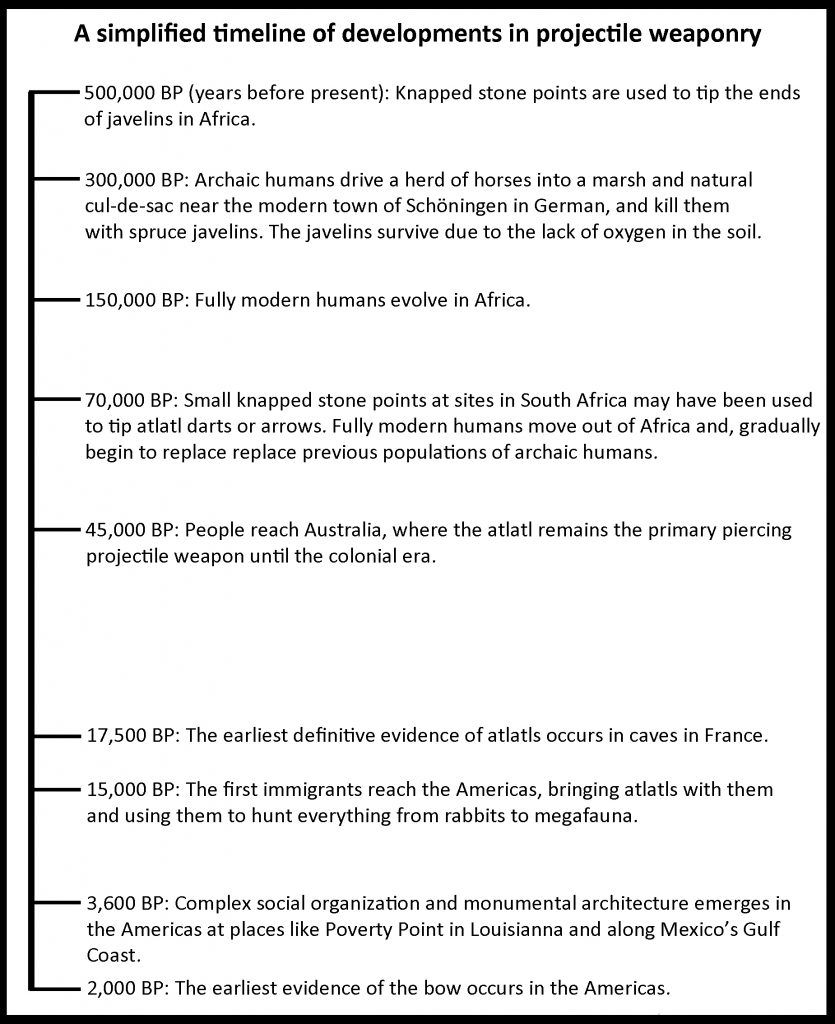

Archaeologists working in southern Africa have proposed that a transition to smaller projectile points ~71,000 years ago at sites like Blombos Cave signifies the development of composite projectiles that were smaller than javelins (atlatl darts or arrows) (Lombard and Phillipson 2010; Marean 2015). Around the same time, our ancestors began their first major push out of Africa. Many scholars subscribe to the idea that more complex tools, social cooperation, and increased resource exploitation allowed us to gradually out-compete and replace older populations of archaic humans (e.g. Neanderthals). These and other developments, such as complex artwork, have been used to define the onset of modern behavior.

However, others claim that the points from southern Africa could be specialized javelin tips. Archaeologists have tried numerous methods to identify what projectile weapons were used by studying the stone points alone, but so far a satisfactory method has not been found (Hutchings 2016). Whatever the case, the new technology did not take hold, at least at those sites. Point types in preceding layers transition back to Middle Paleolithic spear tips. Our species has continued to use “spears” (javelins and lances) into modern times. Some cultures, such as in Polynesia and parts of Australia, used spears and didn’t adopt the atlatl or bow even when they were in contact with people using those technologies. In southern Africa in the 1970s ethnographers found that San hunters were switching more from hunting with bows to hunting with spears for complicated reasons (Hitchcock and Bleed 1997).

Hunting with spears is effective when tactics are used to disadvantage prey, such as driving animals into traps or nets, but in the northern Kalahari hunting large ungulates from blinds had high success rates. In short, we need to look beyond simplified understandings of technological advancement. We need to analyze the specific contexts in which weapons are used. Changes in weapon technology certainly have implications for how people hunt or wage war. But for a long time our species was using a similar technological package to Neanderthals and other Archaic Humans. Archaeologists now recognize some of the evidence used to define modern behavior at Neanderthal sites (Villa and Roebroeks 2014).

Atlatls in the Old World

Identifying atlatl use in the archaeological record is challenging. It requires actual parts of atlatls, which are often constructed of organic materials that only preserve under the right conditions. The oldest known example is a ~17,500 year old osseous hook recovered from a cave in France (Cattelain 1997), although the weapon is probably much older.

Osseous (bone, antler, ivory) hooks in Europe were recognized as atlatl components following colonial encounters with people still using the weapon, such as the Arctic, Mesoamerica and Australia. The 17.5kya atlatl hook from France dates to the Solutrean period, and other atlatl hooks excavated in less controlled digs may date that far back. But most hooks from Europe are associated with the Magdalenian period, when hunting reindeer was an important pursuit. Many hooks were carved into elaborate figures of now extinct ice aged animals. The Mas d’Azil hook depicts a fawn ibex that is defecating and looking over its shoulder at a bird. Three hooks with this same carving have been found in Europe, suggesting it represents a common story (comical?) or myth.

The predominate projectile tips for Magdalenian atlatl darts were also made from osseous materials. Antler is more durable than bone for these projectile points, reindeer antler being the best choice (Guthrie 1983). These points are referred to as sagaies by European scholars. They are generally attached to the shaft with a scarf or V-shaped joint. Some have been recovered with microliths still glued to the side to create a cutting edge (Pétillon et al. 2011).

References on atlatl use in Asia, at least written in English, are harder to come by. The weapon surely had a presence there, as indicated by rock art depicting an atlatl hunter running from an angry rhino in India (Kennedy 2004). The weapon has been found historically on Australia and Papua New Guinea. A lot has been written on atlatl forms and use in Australia (see Cundy 1989; Davidson 1936). They were used for fighting, hunting terrestrial mammals (mostly marsupials) and fishing. The antiquity of the weapon in Australia has been difficult to judge for the same reasons outlined above. It is possible that people were using the atlatl when they first arrived on the continent ~50kya (Marean 2015).

Atlatls in the Americas

In the Americas atlatls have been used to hunt everything from rabbits to blue whales. Heavy darts have proven effective in experiments on elephant carcasses, demonstrating that Clovis people could have effectively hunted megafauna (Frison 1989). Aleutian islanders historically used poison tipped darts to hunt whales from kayaks. In the southwestern US, lighter darts were used with removable foreshafts that could be replaced when points broke, or when a blunt tip was needed for small game. These are the atlatls and darts of the Basketmaker culture. The term Basketmaker is an early 20th c. archaeological designation for pre-pottery hunter-forager-farmers of the US Southwest. Dry conditions in this region have led to the preservation of a large number of prehistoric atlatls, relative to other areas of North America. Most of our replication efforts have therefore been focused on Basketmaker atlatls.

The first immigrants into the Americas from Siberia around 15,000 years ago likely brought the atlatl with them. Atlatl hooks made of mammoth ivory have been found in Paleoindian cultural deposits in Florida rivers (Hemmings 2004). The oldest complete atlatl in North America is from the NV-Wa-197 shaft cave site along the shore of Lake Winnemucca, Nevada (Hester 1974). It is approximately 8,000 years old. Atlatls were not replaced by the bow and arrow in most parts of the Americas until ~1,500 years ago. In many locations, the transition was slow, and both weapons were apparently in use simultaneously. Even after the introduction of the bow, atlatls continued to be used for certain applications, such as waterfowl hunting, marine mammal hunting, fishing, and warfare.

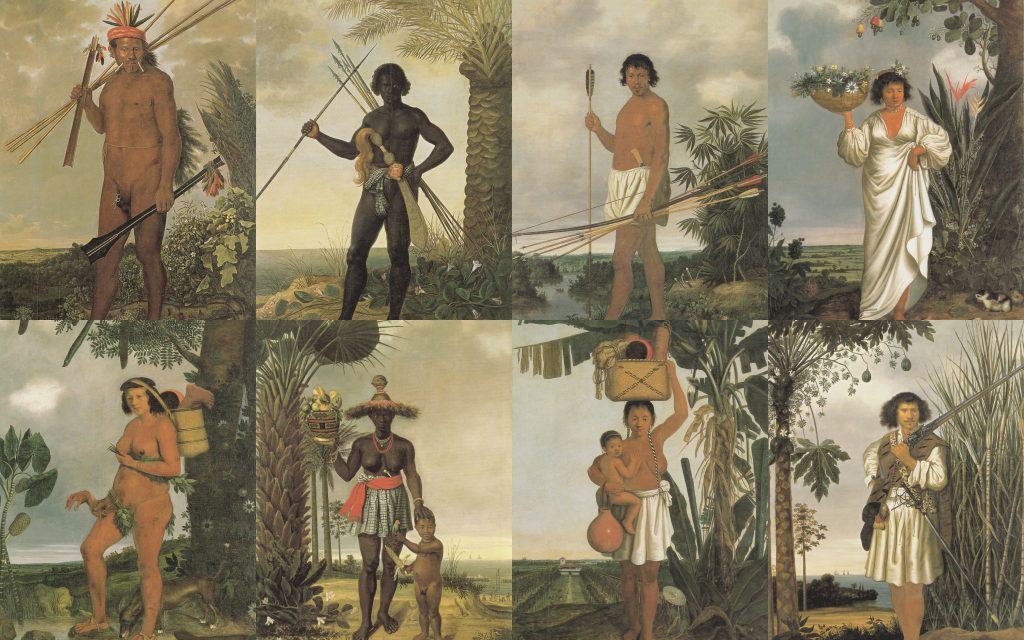

When Spanish conquistadors advanced into Mesoamerica in the 16th c., they met warriors armed with atlatls, and quickly developed a respect for the weapon. Few conquistadors could afford the plate metal armor that could stop darts, arrows and even musket balls! Most wore heavy fabric armor similar to that worn by Mesoamerican warriors, which atlatl darts could penetrate (Pohl and Hook 2001). A conquistador was also hit by a barbed atlatl dart near the mouth of the Mississippi, and died when his comrades tried to extract it (Swanton 1938). And an atlatl was depicted alongside bows on a conch shell at the 15th c. site of Spiro in Oklahoma. Post-bow atlatls have been found on the Baja peninsula (Massey 1961) and in Florida (Whittaker 2011). In colonial Brazil during the 17th c., the Dutch recruited frightening Tarairiu warriors, who used only atlatls for projectiles, as guerrillas against the Portuguese! The Portuguese troops referred to the Tarairiu as the Dutch’s “infernal allies.” They were called Tapuyas by their bow-wielding neighbors, a depreciative term meaning barbarians and enemies (Prins 2010). Atlatls had remained the primary piercing projectile weapon in the Americas for roughly 13,500 years, and continued to be used in certain contexts, even after the bow.

References:

Cundy, B. J.

1989 Formal Variation in Australian Spear and Spearthrower Technology. BAR International Series 546. B.A.R., Oxford, England.

Davidson, D. S.

1936 The Spearthrower in Australia. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 76(4):445–483.

Guthrie, R. Dale

1983 Osseous projectile points: biological considerations affecting raw material selection and design among Paleolithic and Paleoindian peoples. Animals and archaeology 1:273–294.

Hitchcock, Robert K., and Peter Bleed

1997 Each According to Need and Fashion: Spear and Arrow Use among San Hunters of the Kalahari. In Projectile technology, edited by Heidi Knecht, pp. 345–368. Plenum Press, New York and London.

Hutchings, Wallace Karl

2016 When Is a Point a Projectile? Morphology, Impact Fractures, Scientific Rigor, and the Limits of Inference. In Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Study of Stone Age Weaponry, edited by Radu Iovita and Katsuhiro Sano, pp. 3–12. Springer, Dordrecht.

Kennedy, Kenneth A. R.

2004 Slings and arrows of predaceous fortune: Asian evidence of prehistoric spear use. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 13(4):127–131. DOI:10.1002/evan.20007.

Lombard M, and Phillipson L

2010 Indications of bow and stone-tipped arrow use 64 000 years ago in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. http://antiquity.ac.uk/ant/084/ant0840635.htm, accessed September 19, 2011.

Marean, Curtis W.

2015 The Most Invasive Species of All. Scientific American 313(2):33–39. DOI:10.1038/scientificamerican0815-32.

Massey, William C.

1961 The Survival of the Dart-Thrower on the Peninsula of Baja California. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology:81–93.

Pétillon, J. M., O. Bignon, P. Bodu, P. Cattelain, G. Debout, M. Langlais, V. Laroulandie, H. Plisson, and B. Valentin

2011 Hard Core and Cutting Edge: Experimental Manufacture and Use of Magdalenian Composite Projectile Tips. Journal of Archaeological Science 38(6):1266–1283. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2011.01.002.

Pohl, John M. D., and Adam Hook

2001 The conquistador, 1492-1550. Warrior 40. Osprey Pub, Oxford, U.K.

Prins, Harald E. L.

2010 The Atlatl as Combat Weapon in 17th-Century Amazonia: Tapuya Indian Warriors in Dutch Colonial Brazil. The Atlatl 23(2):1–10.

Swanton, John R.

1938 Historic use of the spear-thrower in southeastern North America. American Antiquity 3(4):356–358.

Villa, Paola, and Wil Roebroeks

2014 Neandertal demise: an archaeological analysis of the modern human superiority complex. PLoS ONE 9(4). accessed January 28, 2020.

Whittaker, John

2011 Cushing’s Key Marco Atlatls. Ethnoarchaeology 3(2):139–162.