By Devin Pettigrew and Justin Garnett, updated: 4/20/2020

Atlatl (ahtlatl: Schwaller 2019) comes from Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. This term was adopted by scholars studying Aztec history in the late 19th century and has stuck in the American literature. Atlatls were used for duck hunting and in combat by elite warriors in Mesoamerica. They were also the primary weapons of the gods.

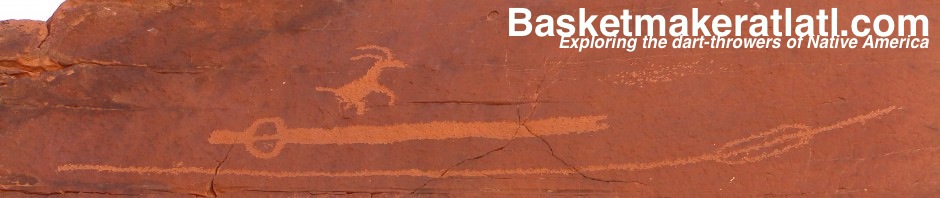

An atlatl is a dart-thrower, a tool by which leverage is used to throw a dart (a light, flexible spear) more effectively than by hand. Atlatls have been used around the world and across time. They have been found on every continent except Africa and Antarctica. It is possible that atlatls were once used in Africa, but making positive identifications of specific weapons from the archaeological record is challenging. Actual atlatls, or identifiable parts of them, are needed. The oldest known atlatl is from Europe and dates to ~17,500 years ago. Atlatls were probably used by the earliest immigrants to the Americas from Asia during the end of the last ice age. They have survived into modern times in the Americas, Australia, and Papua New Guinea (see History of the Atlatl and Advances in Weapon Technology).

How does it work?

All atlatls have an attachment point–this can be a spur or concavity to somehow engage the end of the dart. In most cases this is a “male” spur which couples to a “female” nock at the rear of the dart. The dart nock is held against the spur of the atlatl, and the atlatl is brought forward toward the target, with a final wrist-snap and a follow-through. This throwing motion is not dissimilar from throwing a rock or ball, but affords greater control and leverage on the projectile.

An atlatl works by leverage–by increasing the throwing radius of the user’s wrist. This allows the tip of the atlatl to move much faster than the fingertips of the hand. In simple physics terms, if two points, A and B, are connected to a common axis with A closer to the fulcrum (point of rotation) and B further away, when rotated around the axis, B will always move faster than A. In the real world, one can think of the wrist as the fulcrum, the tips of the fingers as point A, and the spur of the atlatl as point B.

Although the dart is often referred to as a spear and the atlatl as a spearthrower, most darts are light, flexible and fitted with fletchings to improve their trajectory. They are about as similar to javelins as arrows are to darts. The primary difference is in the mode of projection. The atlatl provides greater controllability, and a little more speed over javelins, but not more force on impact. As a result they require less strength and practice to become proficient. The dart must flex in order to account for the arcing motion of the throw and maintain a straight trajectory. Oscillation of the dart on its way to the target can take many forms, including transverse wave oscillation, shaft spinning, and rotating while remaining fully flexed (crankshaft rotation) (Pettigrew et al. 2015). Violent oscillations begin to attenuate within the first few moments of flight. Deviation at the tip of the dart due to oscillation is not much more than 5 cm (see information for hunters, coming soon!).

Atlatl darts launched by practiced individuals usually travel between 50-70 mph (Whittaker et al. 2017). Throws for distance with equipment designed for accuracy and hunting can reach 80 yards. Far more skill is required to master accuracy than powerful throws. During Darwin’s travels on the Beagle in 1836, native Australians could transfix a hat at 30 yards, and an explorer to the Arctic in 1899 was impressed by the accuracy and force of seal harpoons from 30-50 yards (Whittaker 2010). However, the most accurate shots in our experience occur within 10-15m. Whenever possible, native Australians tried to close to these distances before throwing at terrestrial prey (Cundy 1989).

The atlatl is not the ancestor of the bow, its mechanics are completely distinct–the atlatl is not a “Proto-bow.” The bow and arrow makes use of spring-energy, while the atlatl functions by radius extension of the wrist. Some have suggested that the dart springs away from the spur in the final moments of the throw, making the atlatl an energy storage weapon; however, high speed video reveals the dart leaving the atlatl spur fully flexed.

Why study Native American atlatls?

In recent decades the atlatl has been enjoying a resurgence in popularity. There is great interest among many people in using the weapon for target sport and for hunting. There is a lot to be learned from the ancients, those who refined this system initially, so we aren’t all constantly “reinventing the wheel.” That’s concern one, concern two is understanding. The atlatl was an integral part of the pre-contact Native American worldview, and deserves to be understood as well as possible. There are many subtleties in production methods, measurement systems, burial customs, hunting strategy, etc., which could ultimately be inferred though careful analysis of atlatl artifacts. Finally, atlatls are an important tool in the lineage of all modern humans. They are part of our collective cultural heritage.

References:

Cundy, B. J.

1989 Formal Variation in Australian Spear and Spearthrower Technology. BAR International Series 546. B.A.R., Oxford, England.

Pettigrew, Devin B., John C. Whittaker, Justin Garnett, and Patrick Hashman

2015 How Atlatl Darts Behave: Beveled Points and the Relevance of Controlled Experiments. American Antiquity 80(3):590–601. DOI:10.7183/0002-7316.80.3.590.

Schwaller, John F.

2019 The Deeper Meaning of Atlatl. The Atlatl 32(3):1–2.

Whittaker, John C., Devin B. Pettigrew, and Ryan J. Grohsmeyer

2017 Atlatl Dart Velocity: Accurate Measurements and Implications for Paleoindian and Archaic Archaeology. PaleoAmerica 3(2):161–181. DOI:10.1080/20555563.2017.1301133.